Deep Roots

Starting from Brooklyn—and NYU Law—Hakeem Jeffries ’97 has taken his drive for public service and community into the leadership of the House of Representatives.

BY STEPHANIE RUSSELL-KRAFT

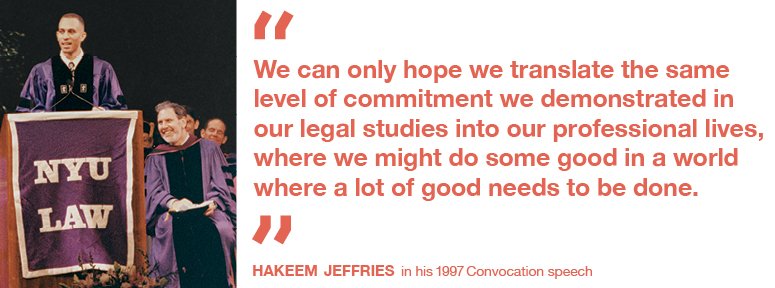

At NYU Law’s 1997 Convocation, then-Dean John Sexton made a prediction. As he introduced the student speaker, he made a point of saying that the 26-year-old—a Vanderbilt Medal recipient and a member of NYU Law Review—stood out for his achievements, “even in this group.” It would be no surprise, Sexton said, if this new graduate eventually served in Congress alongside the main Convocation speaker that year, US Representative Diana DeGette ’82.

Sexton hit the bull’s-eye. More than two decades later, Hakeem Jeffries ’97 is not only serving in Congress alongside DeGette, but chairs the House Democratic Caucus, making him the fifth-highest-ranking Democrat in the US House of Representatives. Jeffries, a fiercely intelligent thinker with a knack for public speaking, has often made his career look easy. But behind his brilliance and charisma is a deep work ethic and a dedication to serving his community. From his childhood in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, to the halls of Congress, he has honed a model of leadership that seeks to find common ground in polarized times.

Addressing his fellow graduates back in 1997, Jeffries described what he called law school’s most important lessons. Learning to put both failure and success into perspective. Building community. Working hard and giving back.

As it turned out, these themes would resonate throughout his own career.

“We can only hope,” Jeffries told his classmates that day, “we translate the same level of commitment we demonstrated in our legal studies into our professional lives, where we might do some good in a world where a lot of good needs to be done.”

Born in 1970, Jeffries grew up in Crown Heights when the neighborhood was being battered by the crack cocaine epidemic. “Those were challenging times,” he says. “There was a lot of dysfunction and pain that surrounded the communities that I was raised in, but also a lot of love and compassion from family and friends, and community folks.” He says his parents, both social workers, didn’t talk much about politics at the dinner table, but their commitment to bettering the world left its mark on Jeffries.

During his senior year at Binghamton University, he watched televised coverage of Los Angeles going “up in flames,” after an all-white jury exonerated four white police officers in the beating of African American taxi driver Rodney King. “It crystallized the fact that we still had a long way to go to eradicate social and racial injustice,” says Jeffries in his characteristically deliberate, thoughtful manner. He resolved to become a lawyer.

He’d already accepted a spot at what is now Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, where he went on to earn a master’s degree. Then he headed to NYU Law, drawn to the school’s public interest program and its clinical courses. Social justice was always on his mind, according to his friend Patrick Michel ’96. “Hakeem was always somebody who wanted to save his people,” Michel says. “That was always who he was.”

Many of Jeffries’s closest friends, including Michel, were members of the Black Allied Law Students Association (BALSA). Jeffries’s voice warms when he speaks about BALSA, which ran community service initiatives, mentorship programs, social events, and sports teams. “You could develop friendships and benefit from the experiences of 2Ls and 3Ls, who had made it through their first year and were willing to help pull you along,” he says of his first year. “It was a great opportunity just to acculturate to the rigors of law school, and have lessons learned past the law.”

Fellow BALSA member Breon Peace ’96 recalls long discussions with Jeffries about a range of issues. “Just the things that he would say would always strike me as incredibly insightful and thoughtful,” says Peace, who also remembers being impressed by Jeffries’s “poise and the way he connected with people in a positive way.”

“We talked a lot about community,” Peace adds. “My father’s a pastor of a church in Brooklyn, and Hakeem was a member of a major church in Brooklyn. And so, we would talk about… relevant issues for Brooklyn, the Brooklyn community, and the role of churches in helping shape the community.”

In the classroom, Jeffries was “the kind of student that makes a teacher’s job really easy,” says Vice Dean and Professor of Clinical Law Randy Hertz, who co-taught the juvenile rights clinic that Jeffries took his 3L year. “In addition to all the things that students are good at, he had a really good sense of how lawyering works in the real world and how to make complicated strategic judgments,” says Hertz.

Jeffries was “fearless” when it came to trying new things, recalls Professor of Clinical Law Kim Taylor-Thompson, who co-taught the clinic with Hertz. “And he just stood out because he put in the work.”

“Without question, the juvenile rights clinic helped me become a better person, a better advocate, and a better lawyer,” Jeffries says. The work he did in the clinic was critical in shaping the criminal justice reform he’s since pushed for as a legislator, he adds.

He also found a mentor in Professor of Clinical Law Anthony Thompson, who joined the Law School in 1996. “Tony Thompson made himself immediately available to know young men of color who were law students at the time, to provide us with advice and guidance as we were moving forward, and that was an invaluable thing,” Jeffries recalls.

As his time at NYU Law came to a close, Jeffries thought about working as a prosecutor for the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, but he didn’t want to leave New York again. Instead, he clerked for Judge Harold Baer Jr. of the Southern District of New York, and then joined Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison as a litigation associate. “I was attracted to the firm because it was one that embraced the notion of the lawyer as public citizen,” he says.

While at Paul Weiss, Jeffries challenged incumbent New York State Assemblyman Roger Green in the Democratic primary. He lost that race by 18 percentage points in 2000 and by an even greater margin when he tried a second time, in 2002. Losing was hard, but it helped him practice resilience. “You lose, you learn from it, you build upon it, you keep moving forward, and at a certain point, opportunity presents itself in a way that will allow you to be successful,” he says.

Waiting for that opportunity, Jeffries took an in-house litigation job at Viacom in early 2004, following an interest in film, music, and popular culture. Two years later, he had another shot at an Assembly seat when Green retired to run for a seat in Congress.

This time Jeffries won. Leaving Viacom, he served three terms in the State Assembly. During that time, he co-sponsored a successful bill to legalize same-sex marriage in New York, and helped write a law that prohibited the New York police department from maintaining an electronic stop-and-frisk database—the legislative accomplishment of which he says he’s most proud. Jeffries says the skills he learned as a young Paul Weiss litigator—marshaling facts, using evidence to persuade others— were invaluable in the Assembly. The biggest difference, he says, was that he no longer advocated for clients, but for constituents.

In 2012, Jeffries set his sights on Congress, running and winning in New York’s Eighth District. His two sons, now teenagers, were young enough to be allowed on the House floor for his swearing-in. “That’s a memory I’ll never forget,” Jeffries says.

He took to Congress two key practices that he’d adopted as a state legislator. Every January, he gives a “State of the District” address in Brooklyn, updating constituents on the previous year’s accomplishments and the coming year’s goals. And in the summer, he hosts “Congress on Your Corner” events, setting up a table outside a local post office or business where constituents can meet with him one-on-one.

“The House of Representatives is designed as an institution that is at its best when it’s closest to the people and reflecting the passions of everyday Americans,” Jeffries says. “In order to bring that to life, you have to be amongst the people as often as possible.”

“He never moved out of Brooklyn, he never took his kids out of Brooklyn,” says Todd Dumas ’98, who lives there and has worked on all of Jeffries’s campaigns. “He has evolved as a legislator,” Dumas adds, “but in terms of his person, he has stayed grounded.”

Jeffries has also stayed true to his Brooklyn roots while he’s in Washington. In 2017, on the 20th anniversary of the Notorious B.I.G.’s death, Jeffries paid tribute to the rapper on the House floor, calling Biggie Smalls’s “rags to riches life story…the classic embodiment of the American Dream.”

“If prominent artists like Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra can receive tributes on the House floor, Biggie Smalls can receive one as well,” Jeffries says.

Following a “blue wave” election in November 2018 in which Democrats took control of the House of Representatives, Jeffries was elected by fellow House Democrats as chairman of the House Caucus. The race was contentious, pitting Jeffries, a relatively young and moderate Democrat, against Representative Barbara Lee of Oakland, a septuagenarian progressive icon and fellow member of the Congressional Black Caucus. Jeffries narrowly won in a 123–113 vote.

Congressman Scott Peters ’84, who represents California’s 52nd Congressional District in San Diego, says he supported Jeffries in the election because of his ability to communicate, not only within the caucus, but with Republicans and the American people. “He’s got the microphone, and we trust him with it,” says Peters. “He’s frankly one of the people I would want telling America how Democrats are going to make things better.”

Jeffries also knows when to sit back and listen, Peters says. Anthony Foxx ’96, former secretary of transportation under President Barack Obama, agrees. “I saw [Jeffries] in meetings quite frequently,” Foxx says, “[and] I noticed a lot of times that he would lay back and let other people make points, even though when you look at him and observe him, you know that the wheels are turning inside that amazing mind of his, and you know he’s figuring out what hasn’t been said that needs to be said, and if he finds that there is something unspoken, he’ll say it.”

In an era of sharp divisions between the two major political parties, Jeffries is clear about where he stands. At the same time, Jeffries doesn’t rule out bipartisanship on certain issues. He advocates what he calls principled resistance.

“When there are principles at stake that are uncompromisable, such as protecting women’s rights, civil rights, reproductive rights, the rights of immigrants, and voting rights, we drew a hard line,” he says. “However, when it comes to working to solve problems like the over-criminalization and mass incarceration epidemic, when there’s an opportunity to find common ground,” he adds, it’s worth working with the other side.

The FIRST STEP Act, signed into law in December 2018, was the result of Jeffries reaching across the aisle. He and Republican Congressman Doug Collins of Georgia’s Ninth District co-authored the House version of the bill. Among other things, the law made thousands of people convicted of drug offenses involving crack cocaine eligible for a reduced sentence, curtailed juvenile solitary confinement, and reduced mandatory minimum sentences.

“It was probably one of the most successful bipartisan efforts of the last Congress,” says Peters. “For him to navigate that and get that to the end was the kind of leadership we’re all kind of thirsty for.”

Another of Jeffries’s bipartisan efforts was the Keep America’s Refuges Operational Act, signed into law in 2018, which reauthorized the National Wildlife Refuge System’s volunteer services, community partnerships, and education programs through 2022. Drawing on his experience as an intellectual property litigator, he also co-sponsored the Music Modernization Act of 2018, a bipartisan federal law that made it easier for copyright owners to be paid royalties when their music is streamed online.

Jeffries also can find common ground across the spectrum of his own party, according to Peters. “There’s a little bit of competition between the center and the left sometimes, and he’s good at making sure there’s communication,” Peters says, adding, “It’s not something that you notice, but you’d notice it if it weren’t there.”

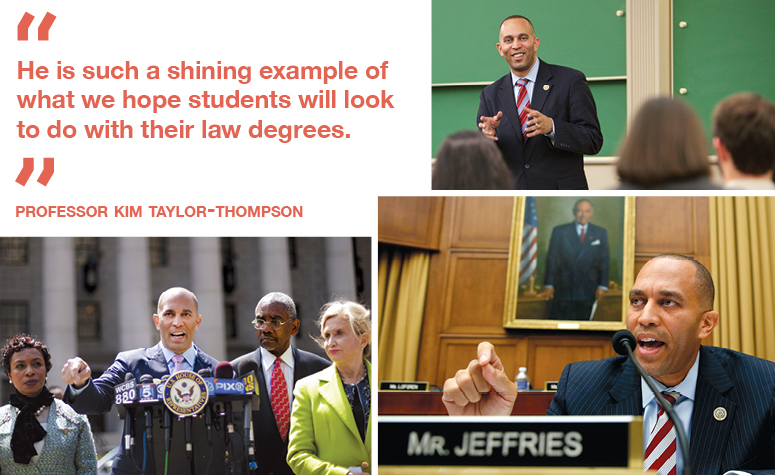

Despite a congressman’s busy schedule, Jeffries maintains strong connections to the Law School, returning every year to speak with clinical law students on campus. Tony Thompson marvels: “That’s one thing for a State Assemblyman or freshman congressman. It’s just insane that he keeps doing that. But he’s committed to the institution and to us.” This year Jeffries made an extra trip back, delivering the JD Convocation address in May.

Jeffries says his only regret from his time at NYU Law was on the football field, where he played on the BALSA intramural team. “Our football team went undefeated in both my second year and third year until we got to the championship game,” he says in a mock-serious tone, “but we lost both times.”

Those defeats aren’t what stand out to Jeffries’s former teammates. They remember his leadership, on and off the field. “He did a great job of bridging gaps and introducing people to one another and creating community,” says James Earl Brown III ’97, another former member of the team. “He is a person who would much rather seek to understand first before trying to be understood.”

Former classmates and professors believe Jeffries could be the next Speaker of the House after Nancy Pelosi. Jeffries demurs: “We all need to remain focused on doing our current job,” he says. Brown says he wouldn’t be surprised to see Jeffries elected to the Senate. “I have no idea if he has aspirations above and beyond that,” says Brown. “But if he did, I wouldn’t be someone who bet against him.”

“I’m loving the fact that people are recognizing what a strong leader he is,” says Professor Kim Taylor-Thompson, adding, “He is such a shining example of what we hope students will look to do with their law degrees.”

Stephanie Russell-Kraft is a freelance writer based in New York.

Posted September 4, 2019

Learn more about how NYU Law prepared Hakeem Jeffries for a career in public service: