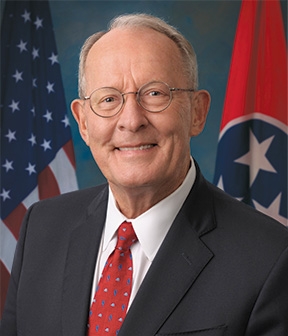

A Q&A with Lamar Alexander ’65

Senior US Senator Lamar Alexander ’65 of Tennessee celebrated his 55th reunion year by reflecting on his career and the value of a legal education in a conversation with NYU Law Magazine.

Why did you decide to study the law, and why is that important? When I was a boy, I read about Clarence Darrow and admired lawyers. I was interested in public life, public service. And my father had worked for a corporation and had always advised me that I should try to be more independent. I thought the legal profession would provide independence.

I had never been to New York City before I enrolled in NYU Law; it was a chance for me to see the rest of the world. And money—I had no money. For all those reasons, I applied for a Root-Tilden scholarship and came to NYU in the fall of 1962.

Do you have any memories of law school you’d want to share? Oh, I have wonderful memories. Arriving in New York City for the first time in my life and taking a cab to Washington Square and looking out the window almost the entire night at all the unusual people who were there until early in the morning. The next day standing in line to enroll to register for classes, there was a tall, skinny guy in front of me who had left his money in New Jersey, which was home. And I loaned him almost all the cash I had for the year, about $300, which caused him to think I was really a rube that I would trust anybody with that much money. And that person was Paul Tagliabue who became my roommate for two years and later the Commissioner of the National Football League.

Having breakfast in a place called The Bagel, which was the size of a closet. Playing basketball with some of the young faculty members, like Norman Dorsen.

I remember my summers. The first summer of ’63 I was an intern for Bobby Kennedy in the Justice Department in Washington, D.C. And I heard Martin Luther King’s “I had a dream” speech. And in the summer of ’64 Paul Tagliabue and I took our roundtrip plane tickets, cashed them in, and rented a blue convertible and drove to Los Angeles and worked for Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher when it had just 40 lawyers.

I remember coming in 21st in an academic class of 300 after the first year and only 20 were selected for the law review. And so I spent my second year down in the stacks reading every en banc Federal Appeals court case and writing a note so I could write my way onto the law review.

I remember touch football with the Yale Law Journal in New Haven when I met Judge John Minor Wisdom of New Orleans and he offered me a job as his messenger, because at the time they only allowed him one law clerk on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. And he said, “I can only pay you as a messenger, but I’ll treat you like a law clerk.” And at night, to make extra money, when I was his law clerk in New Orleans, I played in a place called Your Father’s Mustache on Bourbon Street and I played for whichever band member was absent that night. I played the trombone, and the tuba, and the washboard.

Did you make other lifelong connections when you were at the law school? I did. I made most of my best friends in life in law school. I’ve thought about that many, many times. My wife, Honey, and I celebrated our fiftieth wedding anniversary on January 4, 2019, with several of them at our Tennessee home.

How did the study and practice of law prepare you for your public service career? If you’re a United States Senator, you’re expected to know a lot about a lot of different things and distill information to its essence. And that’s what law school teaches you how to do. Once you understand the problem and figure out a solution, you’ve got to persuade at least half the people you’re right. And law school taught me to think, and write, and speak more clearly. And if your job is writing laws, it helps to know something about laws.

Do you think there’s a particular adaptability that comes with legal training? You don’t learn all those skills as well in other types of training. The skills that you learn at law school and in good legal training are especially well suited to public service. For example, what you learn in business school is not as well suited to public service, and businessmen have a much harder time in public life than lawyers do.

How would you compare the skill set that’s needed to work in business with working in government, as you’ve done both? Well, one, thick skin versus thin skin. Most business CEOs are rarely criticized in public. And most of us in public life are criticized every five minutes. I’ve found that when I serve with people who were once in business, that they’re shocked by the criticism and by how different it is. And I say to them that just because you’ve watched a lot of baseball doesn’t make you a good first baseman. It’s different.

Number two, public life is unscheduled. In a good business you have a schedule, but in public life you have to be very flexible and let the game come to you.

Number three, many people in business are very good at doing one thing very well. And in public life you rarely get to do the same thing over and over again. You have to be flexible and broad-gauged.

Finally, public life is about compromise. How do you become what Senator Howard Baker called “an eloquent listener” and hear the view of the other person and then come to a result? In business often if you’re the chief executive, you develop a strategy and impose a result and make sure it’s done exactly the way you want.

Can you talk about how you think about the role of education and why it has been a focus for you? A lot of public life is about seeing problems and solving them. And in my experience, the solution to most of the problems has to do with education. For example, Tennessee 40 years ago was the third-poorest state based on family incomes, and as governor I tried a lot of things, but the key to higher family incomes was better schools and better colleges and universities. Or when I was a university president, I saw that a college education was the primary engine for helping somebody move from the back of the line toward the front of the line.

And of course, the main reason for education is just simply to make life more interesting and enjoyable.

What would you consider to be the appropriate role of executive power in this equation? When I became governor, someone gave me George Reedy’s book The Twilight of the Presidency. George Reedy was Lyndon Johnson’s press secretary. And he defined the president’s job in this way: Number one, see an urgent need. Number two, develop a strategy to meet the need, and three, persuade at least half the people you’re right. And I used that definition as my formula for how to be a governor. I think that’s what an executive in public life should do.

A hallmark of your time in public service has been an effort to simplify government and engagement with the governed. Why is that important and how are we doing? It’s important because it’s important for people to know what you’re talking about. I can’t tell you the number of conversations I get into in my office when people start talking and I don’t know what they’re talking about, and many times neither do they. Because they haven’t taken the time to boil it down to its essence—which is something you learn in law school—so they can explain it and write about it in plain English. In fact, I have all sorts of graduates from fine colleges who come to my office and want a job who are unable to write a declarative sentence.

Now the downside of simplifying is this: the internet democracy we have today simplifies too much. And most of the issues that we deal with aren’t black and white. The internet democracy puts a premium on instant, quick, certain reactions and in that way makes it difficult to govern. So there’s a plus and a minus to the simplification of public life.

As you come to this stage of your career, is there’s something you’re most proud of? I’ve survived nearly a half century in and out of public life with a family that’s reasonably intact and a reputation that’s reasonably intact. Neither of those is that easy to do.

I think the greatest contribution I’ve been able to make is to remind Tennesseans to celebrate who we are instead of who we’re not. Just doing that has helped us gain a lot of confidence, and the state has been on a very strong track for the last 40 years. When I was recruiting the Saturn plant in the 1980s, I invited Charlie McCoy, who is a harmonica player, to entertain the General Motors executives from Detroit, which embarrassed one of the Nashville guests. She said, “Why would you have that harmonica player? What will these sophisticated people think of us?” And I said, “Madam, why should we offer average Chopin when we have the best harmonica player in the world?”

What gives you hope right now? What gives me hope is my service in the United States Senate and as governor and US Education Secretary and as president of a university. Let me give you an example. Every year I take American history teachers on the floor of the Senate before it opens. And they always ask me, “What do you want us to tell our students?” And I say, “I hope you’ll tell them that I get up every morning thinking I’m going to do something good for the country and I go to bed most nights thinking I have. That we have a remarkable country with 20 percent of the money in the world, the strongest military, the best universities. It’s the best place to start a business. And while our politics and government is rough and tumble, most people would like to swap theirs for ours. And we need to take advantage of it and remember that it’s fragile, and keep it as strong as we can.”

I was attracted to NYU nearly 60 years ago by Dean Vanderbilt’s notion of practicing law in the grand manner, which meant serving in government during part of your life. And I would like to see more NYU graduates serving in government rather than suing the government. I think suing the government can be a noble calling, but we have a shortage of talented people serving in government, and we need talented NYU graduates making decisions about new vaccines, lowering healthcare costs, fixing the national park maintenance backlog. Someone has to run for office or be appointed to office in order to do that. So my hope would be that more talented NYU graduates would want to serve in government at some level during part of their life. I think they would find it very satisfying, and our country would benefit greatly from it.

Posted September 11, 2020. This interview has been condensed and edited.