Emptying the Prisons: Rachel Barkow weighs whether arguments for prison abolition will bring needed change to the criminal justice system—or backfire

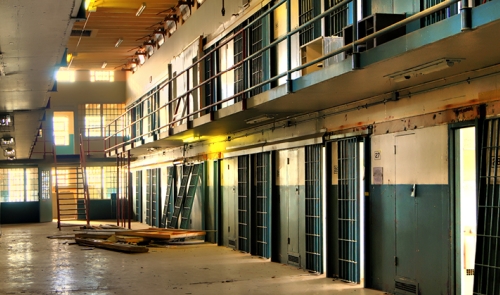

Among the nations of the world, the United States is the world’s largest incarcerator, with 1.9 million people—565 per 100,000 residents—in prison or jail. To combat what they see as the abuses and overreach of the current carceral system, some criminal justice advocates have proposed its abolition.

In a forthcoming paper in Wake Forest Law Review, “Promise or Peril?: The Political Path of Prison Abolition in America,” Charles Seligson Professor of Law Rachel Barkow explores the potential impact of the prison abolition movement: Will it lead to productive changes in the criminal justice system—or instead produce a backlash that hinders reform efforts?

The faculty director of the Zimroth Center on the Administration of Criminal Law, Barkow served as a member of the US Sentencing Commission from 2013 to 2019 and is the author of Prisoners of Politics: Breaking the Cycle of Mass Incarceration. Analyzing the pros and cons of arguments for prison abolition, her paper applies lessons from the “defund the police” movement and the deinstitutionalization of mentally ill populations. While ending mass incarceration has been a longtime focus of Barkow’s scholarship, she concludes her analysis by finding significant political and practical risks in proposed abolitionist solutions.

What kind of data did you analyze to weigh the pros and cons of prison abolition as a movement tactic?

There are no empirical studies or polling data on prison abolition, so you have to extrapolate from other sources. We have some information on the “defund the police” movement and its successes and failures. The most notable failure is the blowback that has led to police departments seeing increased funding and state-level efforts to block local law enforcement budgets from ever being reduced below certain levels.

I also look closely at the movement to deinstitutionalize state mental hospitals in the 1960s and 1970s because there are strong parallels between it and prison abolition.

In addition to looking at those two analogous frameworks, I consider the politics around crime and punishment more generally to consider how abolitionist arguments are likely to play out. The public looks to punishment to serve various purposes, particularly the utilitarian goals of deterrence and incapacitation, and the retributive goal of meting out just desserts. The article considers what prison abolitionists have said will replace the prison to serve those same ends to determine if those claims will resonate broadly enough with voters and diverse community interests.

You note that the deinstitutionalization movement of the 1960 and 1970s, which advocated for the transfer of mentally ill people from state mental hospitals back to their families or into community-based homes, should serve as a “cautionary tale” for future abolitionist movements. What are the lessons of deinstitutionalization?

There are lots of lessons from deinstitutionalization. The first one is that it is easier to end something than to fund something. So while the deinstitutionalization advocates achieved the agenda of closing hospitals, they failed in getting community health centers and other alternatives to serve the needs of people previously in state hospitals. That’s an important lesson for prison abolitionists because their agenda depends upon addressing the root causes of crime, which would require massive amounts of state funding.

Another key lesson of deinstitutionalization is to be attentive to variation in the population you are trying to help. Deinstitutionalization advocates tended to ignore people with the most serious mental health needs because those people disrupted the simple narrative they wanted to use, which was that mental hospitals were not necessary. Unfortunately, some people do need custodial care given their serious mental health problems. That message was more complicated than political advocates wanted, however, and so those people fell through the policy cracks when hospitals were closed. It is a big reason so many people with serious mental health problems are unhoused and without any services today.

Prison abolitionists face a similar danger because they focus on people who commit crimes because of structural inequality. They argue if we fix those root causes, we won’t have crime. Unfortunately, though, that is not the only cause of crime. We have people who harm others because of greed, lust, jealousy, vengeance, religious and political ideology, and any number of other factors. Structural fixes won’t stop that, so there needs to be a societal response that deals with people who would harm others for those reasons.

A third key lesson is that relying on the “community” to address the problem might not work. Deinstitutionalization advocates focused on community support, but that support did not materialize. Prison abolitionists likewise speak vaguely of communities filling in key gaps for the state, but there is a real question mark whether that could happen in a society as complex and diverse as ours.

Are there common misconceptions about the policy implications of an abolitionist framework, or the prison abolition movement itself?

I think one misconception about the prison abolition movement is that it is a monolith, when in fact lots of different people and groups identify as abolitionists but mean very different things when they use the term.

Some people give the word its commonly understood meaning and seek to end the use of all prisons. Others, however, see abolition more as a guiding principle but do not necessarily think it will mean the end of all forms of incarceration. They might be willing to accept some form of liberty restriction for what they tend to call “the dangerous few.”

I tried to be an honest broker in discussing the variation in the movement and the different claims and ideas that have been set out under its umbrella.

Why did you choose to write on prison abolition?

I have spent my career thinking of how we could end mass incarceration in America and radically decarcerate. I have worked on these issues as a scholar, as a policy advocate, and in the government. So these are more than abstract questions for me. They are politically urgent issues, so my goal in writing this paper was to think deeply about how abolition will shape the agenda. I tried to lay out both possible scenarios given the political landscape we live in—the more optimistic take and the more pessimistic one. While my analysis concludes the more pessimistic vision is the more likely path—in which calls for abolition lead to more harms than they prevent—I would be more than happy to be proven wrong.

Posted March 30, 2023