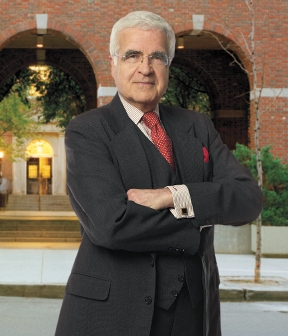

Don’t Blame (Just) the Lawyers: Assisted by students, Arthur R. Miller assesses responsibility in the litigation “cost and delay” narrative

When a major brief needs to be filed in a lawsuit, law firm partners commonly assemble a team of associates to get the job done. As University Professor Arthur R. Miller sees it, the student research assistants who worked for him last summer had a similar experience.

The project materialized after the Cardozo Law Review asked Miller to write an article addressing a longstanding critique of litigation: resolving disputes in the courts costs too much and takes too long. In particular, the editors sought his reaction to a piece they published in 2016 by Victor Marrero, a senior judge of the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, that blames “wasteful” practices by lawyers—filing “fishing expedition” complaints, for example, or pursuing endless discovery.

Given his many other commitments, Miller was initially inclined to turn down the request. Then the judge himself asked Miller to contribute. “I have always had this rule: Never say no to a federal judge,” Miller says. Each summer, Miller employs student RAs to update the legendary multivolume treatise that bears his name, Federal Practice and Procedure, Wright & Miller. For his seven summer 2018 RAs, Miller thought, the opportunity to also work on the article was unique and “consistent with the idea that I owed them some mentoring.” They agreed to take it on, allowing Miller to tell Judge Marrero yes.

After providing the students with a general sense of the issues he wanted to address, Miller asked them to divide the work among themselves. Each student produced a one-page outline and then a first draft of his or her assigned section. “Interact with each other in terms of precisely what you think is covered by whom, and don’t be embarrassed and don’t get your ego involved,” Miller recalls telling them.

“I did have in the back of my head my own experience of how, in big-time law practice, briefs are often put together on a collaborative basis,” he says. “You have to learn how to work and play well with others.”

Once he had reworked the students’ submissions—incorporating his own thoughts, adding additional subjects, and putting the piece in his own voice—Miller asked the RAs to suggest edits. The final version, “Widening the Lens: Refocusing the Litigation Cost-and-Delay Narrative,” was published by Cardozo this month.

The article questions the factual bases of the “so-called cost-and-delay narrative,” noting that its champions tend to be “defendants and conservative political forces” who are generally hostile to lawsuits. But even acknowledging that litigation can be protracted and expensive, and that lawyer behavior may be partly responsible, the piece documents other factors contributing to the problem. It notes, for example, that some procedural changes adopted by courts to allow judges to dispose of cases more quickly (such as revised pleading and summary judgment standards) may have had the opposite effect.

In Miller’s view, those changes have also led to something that dismays him more than cost and delay: the steady erosion of people’s ability to bring their disputes to court in the first place. It’s a topic he discussed in his March 2012 lecture, “Are They Closing the Courthouse Doors?” and reprised in the “Widening the Lens” article. “I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to use this as a stepping off point to do my own thing, to reflect my own distress,’” Miller says.

As a teacher, scholar, and practitioner for more than 50 years, there is little about the litigation process that Miller has not had the opportunity to examine, from the nuances of a single rule to broader concerns such as access to justice. His RAs this summer got a crash course that offered both perspectives. “My work on the treatise was focused on highly specific areas like alienage and admiralty jurisdiction,” notes Katie McFarlane ’20. “Conducting research for the article allowed me to take a step back and evaluate the operation of the entire system as a whole.”

The opportunity to work as a team was also instructive. “There was a good deal of collaborative writing, but generally we maintained ownership over our initial sections, even as things moved around through the drafting process,” says Eugene Woo ’20. “As a learning experience, I felt like I got valuable exposure to doing more academic research and writing. And as a life experience, I learned that we can accomplish things no matter how little we know or how daunting the task seems at square one.”

Posted December 4, 2018