With Environmental Rollbacks, Communities of Color Continue to Bear Disproportionate Pollution Burden

Brittany Whited / June 19, 2019

Artwork created by Ricardo Levins Morales, 2006 — you can support the artist here.

Juneteenth is the most popular annual celebration of emancipation from slavery in the United States. Juneteenth doesn’t mark the signing of the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, which technically freed slaves in the south, nor the surrender of the Confederate army in April 1865, nor does it commemorate ratification of the Constitution’s Thirteenth Amendment that abolished slavery. Instead, it marks the day when news of emancipation finally reached 250,000 slaves in Galveston, Texas, part of the former Confederacy, on June 19, 1865.

In many ways, Juneteenth represents how justice in the United States has repeatedly been delayed for black people, and access to a healthy, safe environment is no exception. This history makes the current administration’s repeated, unlawful attempts to weaken our nation’s bedrock environmental laws and undo important progress to ensure clean air, water and a healthy environment across the country all the more troubling. Rollbacks of lifesaving checks on some of the nation’s biggest polluters — coal power plants and cars — increase the already-disproportionate environmental burden on black communities.

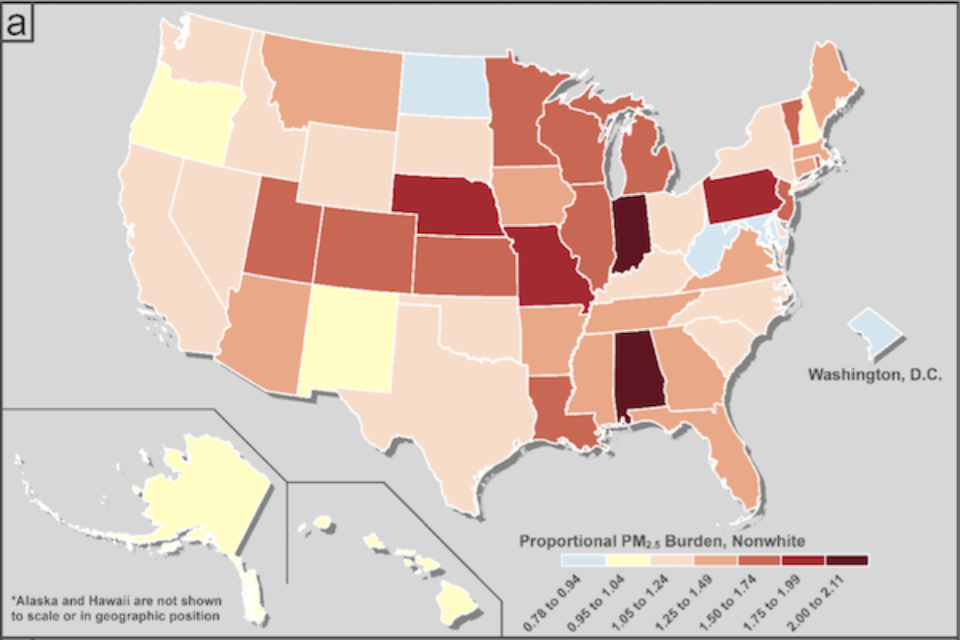

In the United States, black people are 54 percent more likely to be exposed to air pollution in the form of fine particulates (PM2.5) compared to the overall population. Exposure to PM2.5 is associated with lung disease, heart disease and premature death. African Americans are nearly three times more likely to die from asthma — also linked to poor air quality — than whites.

Figure: Map of Proportional Burdens for Nonwhite Populations in PM2.5 Emissions

In all but four states (MD, NM, ND, and WV, as well as Washington, DC), people of color have greater PM2.5 exposure compared to white people. In some states, like Indiana and Alabama, people of color are exposed to at least twice as much PM2.5 pollution. Mikati et. al, supplemental materials.

Historical racism and economic inequality are major factors behind these disparities, as polluting facilities and areas with heavy traffic are generally located near communities of color.

Environmental racism — the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on people of color — doesn’t stop at air quality. Racial minorities are more likely to live near toxic sites and landfills, drink unhealthy water and have elevated levels of lead in their blood. These disparities can be addressed by implementing and enforcing environmental laws and regulations in a manner that equally protects everyone — a concept called “environmental justice.”

Unfortunately, many federal regulations that could make our environments healthier are being stalled or rolled back. The Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) announced that it has finalized its rule rolling back power plant emission standards today, and has previously signaled its intention of finalizing fuel efficiency standards later this summer. By the EPA’s own calculations, repealing and replacing the Obama-era standards on coal fired power plants (called the “Clean Power Plan”) could lead to as many as 1,400 premature deaths annually by 2030 from PM2.5 pollution, up to 15,000 new cases of upper respiratory problems and tens of thousands of missed school days. The rollback of fuel efficiency standards would lead to 300 premature deaths annually by mid-century. The burden of this pollution will disproportionately fall upon communities of color.

To make matters worse, the Trump administration has taken additional steps to reverse important progress in ensuring clean air and clean water for all. The first White House budget proposed eliminating the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice, and the EPA has failed to address community concerns over landfill and toxic waste development in minority communities.

To address inaction and backtracking on environmental protections at the federal level, many environmental groups, community leaders, cities and states have stepped up. At the state level, attorneys general have been standing up for environmental justice to ensure that everyone can live, learn, work and play in an environment that is healthy and safe. On the regulatory side, states are offsetting federal rollbacks — California and 13 other states have pledged to fight for stricter fuel efficiency standards and less air pollution in their states. States have also opposed nearly every environmental rollback from the current administration, including attempted rollbacks of national water protections, emission standards for landfills and asbestos reporting.

Attorneys general in New Jersey and California are embracing action by establishing environmental justice divisions within their offices and targeting polluters in minority and low-income communities. Even without established environmental justice offices, protecting traditionally overlooked communities is at the core of many attorney general actions. In New York, for example, Attorney General Letitia James secured settlement funds from Clean Air Act violations to fund a fleet of all-electric, zero-emission delivery trucks in New York City. Because low-income communities and communities of color have high truck and traffic volume, reducing pollution from diesel trucks can have an especially large impact in these communities.

Attorneys general have also advocated for equal access to the country’s treasured natural resources. When the National Park Service sought to increase park entrance fees in 2017, attorneys general argued against the increase, stating that increased fees would reduce access to National Parks for groups that are already underrepresented in national park usage, including people with low incomes and communities of color. In the end, instead of increasing by $45, park fees only increased by $5.

The United States has a long history of overlooking communities of color, and environmental justice problems cannot be solved by states alone. There remains a significant amount of work to be done, and state attorneys general will continue to be part of the fight for environmental justice until all people enjoy access to a safe, healthy environment.